Tape 118 – Haircuts: Oh, There I Am

This week I got my hair cut, which is something I do periodically in order to make myself look slightly less shit. For this particular haircut, my barber wordlessly summoned a nervous-looking young man to his side, to which he stuck assiduously for the entire duration of the process, never once tearing his eyes away from the barber’s hands. I assume that this was a relationship founded on some sort of apprenticeship or training scheme, though I may be wrong. He may simply have been my barber’s friend, and this might have been their idea of a good time. I had never texted my friends to invite them to my place of work in order to wordlessly stare at my hands for twenty minutes, but it takes all sorts to make a world, after all, and I’m sure if some people were flies on the wall watching me interact with my friends, they’d find some things that seemed totally normal to me but impenetrable to them (me and a friend once spent more than one hour wiping a wall with a cloth while singing “We like wiping walls,” and we were not cleaning the wall. We were just wiping it).

Nonetheless, I assumed that I had become an Object of Study in this young trainee barber’s professional education, and I felt the thrill of flattery – my barber had chosen my head as a suitable object on which to place this burden of responsibility, like the most honourable of hats! If I played my cards right and made myself into an exemplary subject, I could become a core memory for one of London’s leading barbers of the future. I channelled all my energies into being friendly and accommodating, in the hope that after I left, the young apprentice might turn to his boss, starry-eyed, and say “Wow, I sure hope I get lots of customers like that when I’m a proper barber. He was brilliant.”

What, then, could I expect this young man to learn from me, watching me from the outside-in? What had my own personal experience in the barber’s chair led me to represent that he might be able to discern?

The image in your mind wobbles. We are in a flashback.

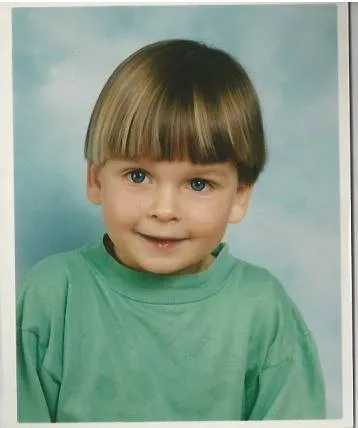

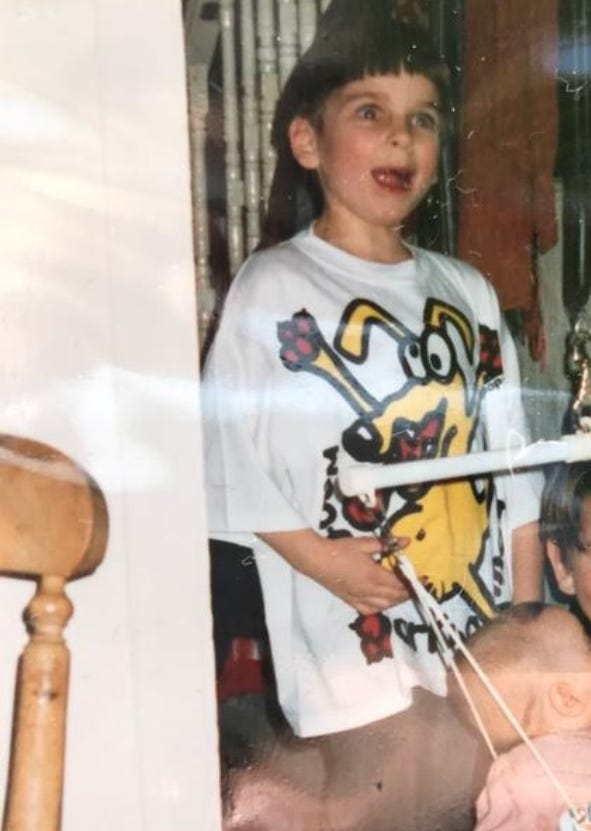

Until I was about seven years old, my mum cut my hair using a pudding bowl, as I believe was standard practice for all millennials. I no longer see children with this haircut, which makes me sad. My wardrobe consisted largely of my school uniform, and little else. When I was around eight years old, I decided to radically “rebrand” myself. I got my hair cut by an actual hairdresser named Ricky (you also don’t meet Rickies any more), and requested it be short and, in my own words, “sticky-uppy.” A lot of my favourite pop culture figures at the time had sticky-uppy hair (Tintin, Mark Speight, Gary Rhodes – it’s only as I type this out that I realise with a sickening chill that every single one of these heroes of mine that ever lived as a flesh-and-blood, non-fictional person has since died tragically young), and I wanted to join their ranks (in the sticky-uppy hair stakes, not the dying young bit). To accompany my radical rebrand, my mum bought me a T-shirt with a “wacky-looking” yellow dog on it, which said “I’m Barking Mad.” You could see the dog’s little willy flapping about, which my mum and I thought was hilarious. In hindsight, the dog looked more rabid than anything else, but I thought it was a really funny T-shirt. I also requested that Mum buy me a pair of shorts covered in bright pink skulls. I decided that my core personality trait from now on was going to be “Insane.” I wanted everyone to know how insane I was.

When I was preparing to debut my new look at a friend’s birthday party, I excitedly told my mum on the way there that none of my friends would recognise me and I would have to explain to them all who I was, and she said she doubted that because I had a face. When I got there, everybody greeted me by name and didn’t even mention my new look, because it was a fancy dress party. I was devastated. I decided I would show them all what this new personality of mine could do, and proceeded to tear up the dancefloor during the disco section. When I described it to Mum later, I summed up my style by saying “I just did a load of spins and slides.” The DJ gave me the prize for the best dancer, saying into the microphone “This kid was going absolutely crazy out there. Where did you learn to dance like that?” I nonchalantly replied “Oh, I just tried to dance like Sting.” I had never seen any footage of Sting dancing, but when I listened to him on cassette in the car I got a clear idea of what I thought he would do (spins, slides). I rarely saw any pictures or footage of the singers I listened to, and tended to prefer conjuring up my own idea of what they looked like based on how their music made me feel. I can still remember the feeling of horror I felt when I first saw a picture of Elton John and realised I’d been getting him completely wrong.

Me pre-and-post-rebrand, the 90s. You’ll notice that in Photo 2 I still have the pudding-bowl haircut, but have acquired my wacky T-shirt and, crucially, demeanour, so photo 2 is sort of mid-rebrand, I think.

As I got older, my approach to haircuts became less radical. I no longer viewed them as opportunities to completely rewrite my identity. I started viewing them as cynical exercises in accounting. My intention, going into every haircut, was to maximise the amount of time between this haircut and my next haircut, thereby saving precious pounds. I therefore always insisted that whatever barber I visited cut my hair significantly shorter than they thought was wise, and walked out of every haircut resembling a large, delighted brush. I always looked terrible after these haircuts, but I would go around confidently claiming that the point of a haircut was to look good about a month afterwards. Because of this, I never had a regular barber, because every barber I interacted with seemed faintly depressed as I said goodbye, as though they knew they had just sent out into the world a walking warning to others to avoid their business. I had to establish a new rapport with a new barber every time I got my haircut, something I was singularly ill-equipped to do.

There was also the slight hiccup that during my teens, when my mum had resumed cutting my hair for me, she once accidentally slipped with the clippers and gouged a deep scar into the back of my head, which now manifested as a small bald spot at the back of my skull. I was usually able to cover it up with my hair, but whenever each new barber uncovered it, they would always stop and stare at it, then make eye contact with me in the mirror, as though trying to work out if it was something they had done that they now needed to try and get away with. I always tried to remain unreadable in these moments, and to simply smile at them encouragingly to see what they would do. It may well have been this degree of obtuseness on my part that made it hard for me to ever truly bond with a barber. (The gouge has now healed sufficiently that the bald spot is no longer apparent, though if I ever shave my head I’m sure I’ll be surprised by whatever scar tissue is lurking under there).

Whenever I went to a new barber, I was always aware of the strange relationship between me and them as creator-and-subject. When I went into a barber’s, it was to solve the problem that when I looked in the mirror I no longer saw myself. I saw myself obscured by hair that didn’t feel like it was mine, it was somehow obscuring my essence, because the length and style of my hair is a part of my appearance, and my appearance is a part of who I am. I’d go in there knowing that I was underneath all that hair somewhere, and needed to be excavated. I needed the barber to find me, and bring me out. It was their job to get rid of my hair until I recognised myself in the mirror and said “Yes, there I am, thank you.” But the barber was like a rescue diver – they had no idea who was in there. “Oh, is that what you look like?” they might think as I finally appeared. “I had no idea that’s what I was working towards.” Or perhaps they felt more like sculptors, bashing away at the lumpen object of my hairy head like they were hacking at a rock until the shape of their imagined sculpture had been exposed. Eventually, I learned to just go in with a photo of myself with my hair at the desired length, and we would agree on it before anything was done, like a prenuptial agreement, which I imagine removed all sense of creative discovery for them and rendered the experience totally devoid of meaning.

I finally found a barber who I wanted to commit to when I moved to Earlsfield in 2019. He was an elderly, eccentric Greek man who owned a parrot that he had taught to say the word “Help,” which it would squawk as soon as you walked in, which I thought was brilliant. I had always struggled to work out what to say in order to fill the space during a haircut, and this barber solved my problem for me by narrating an outlandish, uninterrupted, imagined story about my own life every time I visited.

“You are getting your hair cut for a special occasion?” he asked when I first sat down in his chair.

“Oh no, nothing special,” I said awkwardly. He nodded sagely, closing his eyes, and in fact started cutting my hair with scissors before opening them again, which was slightly nerve-wracking.

“You are getting your hair cut for your mother-in-law,” he said. “Your wife is pleading with you, you gotta make an effort for my mama. You going round for dinner, you gotta look the part. Your sister is gonna be there. Your sister’s new boyfriend gonna be there. Your sister’s boyfriend – he’s no good. He doesn’t treat her right. He doesn’t buy her flowers. He doesn’t treat her nice. You keep telling her, you gotta get rid of this guy. Your mama don’t approve of this boy, she knows her daughter gotta have someone better than this. And your wife, she say, what, you wanna disappoint my mama the same way he disappoint yours? The last time you go for dinner, you don’t make any effort. You don’t treat her right in front of her mama, you don’t tell her mama she look beautiful. So your wife, she throw you out. You pack your stuff up into six bin bags. You sleep on your sister’s sofa, you say, “I gotta win her back.” Your sister say, “Ok, here’s what you do. You take these bin bags, you go back to her place. You get down on your hands and knees and you beg like a dog” (Side note – it has always fascinated me that he said “hands and knees.” In his story, I am not on my knees begging for forgiveness like a suppliant, I am literally on all fours doing an impression of a dog. He went on -). “You say please, baby, please, you gotta take me back.” (Imagine me doing this on all fours like a dog). “It’s no good out there, on the streets. It’s no warm, it’s no nice. And your wife say ok, you get another chance, but you gotta make an effort with my mama. And that’s why you gotta have a haircut.”

“Help!” squawked the parrot as he finished his story (which I have heavily abridged). For 18 months, I continued visiting the same barber. My philosophy of looking shit in order to save money no longer applied. I loved this man enough that I was willing to let him cut my hair the way he wanted. Eventually, I moved away from Earlsfield and had to find a new regular barber. My current barber in Kentish Town never says anything to me, and actually doesn’t realise I am a regular – he is visibly shocked every time I present my loyalty card to him for him to stamp. But, though I miss the ramblings of my old barber, I like my current one because you get a free can of cherry-flavoured energy drink every time you go. They introduced this new deal after putting up their prices by £1 and, even though the energy drink has “75p” printed on the side of it, I still think it’s a good deal.

All this and more floated through my head as my barber silently cut my hair with the diligence of an assassin, and his apprentice trembled with nerves, clutching at his elbow. As I watched him finish up in the mirror, I suddenly connected two thoughts and realised why the barber’s chair has been such a site of personal introspection throughout my life – it’s one of the only places where, for a prolonged period of time, external circumstances cause my inner realities and outer realities to match. I have often tried to articulate in my work the fact that I do not feel like my self – I do not feel like my body, or my hands, or my eyes, or my head. I don’t even necessarily feel like my mind, and I doubt the existence of my soul. Despite all the things I’ve written in which I try to articulate “what it feels like inside my head,” I don’t actually feel like I am inside my head. The closest thing I can describe to how I feel is that I feel like a small point of light hovering eternally somewhere just outside my body, observing what it does. “Don’t do that with your face,” I’ll say to it. “What are you doing with your hands, keep your fucking hands still. Your back is not where you think it is, move your back. I know it feels wrong, but where you’re currently putting it is not right.” Sitting in a barber’s chair, then, feels somehow familiar to me – it’s not often we’re forced to stare at ourselves for twenty minutes at a time, but the thought “Oh, there I am, I’m over there,” is one I’m acutely aware of. It’s how I feel most of the time.

Life often feels like a force I am observing, that I am not always in control of. It’s a story I am telling to myself. I’m sure many comedians and writers feel the same, otherwise why on earth do we feel compelled to make a record of everything we do, to chronicle ourselves as if we’re being viewed from the outside in? Why don’t we just live? I often have to remind myself that my life is just something that is happening to me, minute by minute, and that it’s not a story, it’s just a series of bewildering experiences. I have to remind myself that not only am I the only person who can do anything about my experience of the world, I’m also the only person who has any particular interest in it. I find that the moments where I remind myself of this are often the happiest ones. They’re the moments where I invite myself back into my body, to sit, and look out, and see what’s really there. “Here you are,” I tell myself, “Here you are.”

A Cool New Thing In Comedy – If it’s ok, I’m going to use this section to plug my new work-in-progress show at the Pleasance tonight and tomorrow. I’d love you to come along if you fancy it!

What’s Made Me Laugh The Most – I really enjoyed the live recording of Alexander Bennett and Andy Barr’s Born Yesterday podcast last night, which is an excellent format if you’ve not heard it, and really enjoyed the image of ET enjoying a touch pool at a Sealife Centre. I don’t know why I find it so funny. Imagine him sticking his long finger in to stroke a crab. It’s quite beautiful.

Book Of The Week – Currently reading Wild Card: Let The Tarot Tell Your Story by Jen Cownie and Fiona Lensvelt, because I’m afraid I have gone full tarot wanker.

Album Of The Week – Off the back of getting into King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard last week, this week I’ve been listening to Flying Microtonal Banana, which I don’t like as much as Nonagon Infinity. A few of you did reply telling me which of their albums to listen to next, though, so thanks for your advice, I will continue getting into them! Their discography is quite daunting, so I appreciate the help.

Film Of The Week – The Lesson, which is a really enjoyable thriller by Alice Troughton starring Richard E. Grant as a narcissistic novelist grieving for his son. The third act is a bit hammy and ridiculous, and hinges on a truly ludicrous plot point, but I really enjoyed the film overall, and Grant is brilliant in it.

That’s all for this week! As ever, please let me know what you thought, and if you enjoy the newsletter enough to send it to a friend or encourage others to subscribe, I’d hugely appreciate it! Take care of yourselves until next time and all the best,

Joz xx

PS The short film that Miranda and I made earlier this year is very close to completion, and we’re hoping to unveil it to the world in November. Here’s a sneak peek: